Integrating Data with React Native

This is a series of tutorials designed to introduce React Native and its Open Source ecosystem in plain English, written alongside the building of the F8 2016 app for Android and iOS.

React, and by extension React Native, allows you to build apps without worrying too much about where your data is coming from, so that you can get on with the business of creating the app's UI and its logic.

In the first part, we mentioned how we were adopting Parse Server to actually hold the data, and we would use Redux to handle it within the app. In this part, we'll explain how Redux works within React Native apps, and the simple process of connecting Parse Server.

Before we discuss Redux, let's take a journey to show how React's integration with data evolved to create Redux itself.

First, how do React apps interact with data?

React is frequently mentioned as being the 'View' in the Model-View-Controller (MVC) app architecture, but it is more subtle than that - React essentially rethinks the overall MVC pattern into something else.

Let's first examine the idea of MVC architecture:

- The model is the data.

- The view is how the data is presented in an app.

- The controller provides the logic for handling data within the app.

React lets you create multiple components which are combined to form a view, but each component can also handle the logic that a controller might have provided. For example:

class Example extends React.Component {

render() {

// Code that renders the view of the existing data, and

// potentially a form to trigger changes to that data through

// the handleSubmit function

}

handleSubmit(e) {

// Code that modifies the data, like a controller's logic

}

};

Each component in a React app is also aware of two different types of data, each having different roles:

propsis data which is passed into a component when it is created, used as the 'options' which you want for any given component. If you had a button component, an examplepropwould be the text of the button. A component can't change itsprops(ie. they are immutable).stateis data which can be changed over time by any component. If the button example above was a login/logout button, then thestatewould store the current login status of the user, and the button would be able to access this, and modify it if they clicked on the button to change their status.

In order for React apps to reduce repetition, state is intended to be owned by the highest parent component in the app's component hierarchy - something we'll refer to as container components elsewhere in this tutorial. In other words, you wouldn't actually put the state in the example button component mentioned above, you'd have it in the parent view which contains the button, and then use props to pass relevant parts of the state down to child components. Because of this, data only flows one-way downwards through any given app, which keeps everything fast and modular.

If you would like, you can read more about the reasons and thinking behind these decisions in the Thinking in React guide from the React site.

Storing State

To further explain techniques for data use in React apps, Facebook introduced the Flux architecture which was initially a pattern to implement in your apps, rather than an actual framework to use. We aren't using the Flux library in our app, but the framework we are using, Redux, is derived from the Flux architecture, so let's dig into it.

It expands on React's data relationship by introducing the concept of Stores, containers for the app's state objects, and a new workflow for modifying the state over time:

- Each Store in a Flux app has a callback function which is registered with a Dispatcher.

- Views (basically React components) can trigger Actions - basically an object which includes a bunch of data about the thing that just happened (for example, maybe it might include new data that was input into a form in the app) as well as an action type - essentially a constant that describes the type of Action being performed.

- The Action is sent to the Dispatcher.

- The Dispatcher propagates this Action to all of the various registered Store callbacks.

- If the Store can tell that it was affected by an Action (because the action type is related to its data), it will update itself, and therefore the contained

state. Once updated, it'll emit a change event. - Special Views called Controller Views (a fancy term for the container components we mentioned above) will be listening for these change events, and when they get one, they know they should fetch the new Store data.

- Once fetched they call

setState()with the new data, causing the components inside the View to re-render.

You can see how Flux helps to enforce the one-way flow of data within React apps, and it makes the data part of React much more elegant and structured.

We aren't using Flux, so we won't get into more detail in this piece, but if you want to learn more about it, there are some tutorials on the Flux site to read.

So how is Flux related to Redux, the actual framework we are using in our app?

Flux to Redux

Redux is a framework implementation of the Flux architecture, but it also strips it down, and there are official bindings provided by the react-redux package which make integrating it with React apps much easier.

There is no dispatcher in Redux, and there is only one Store for the state of the entire app.

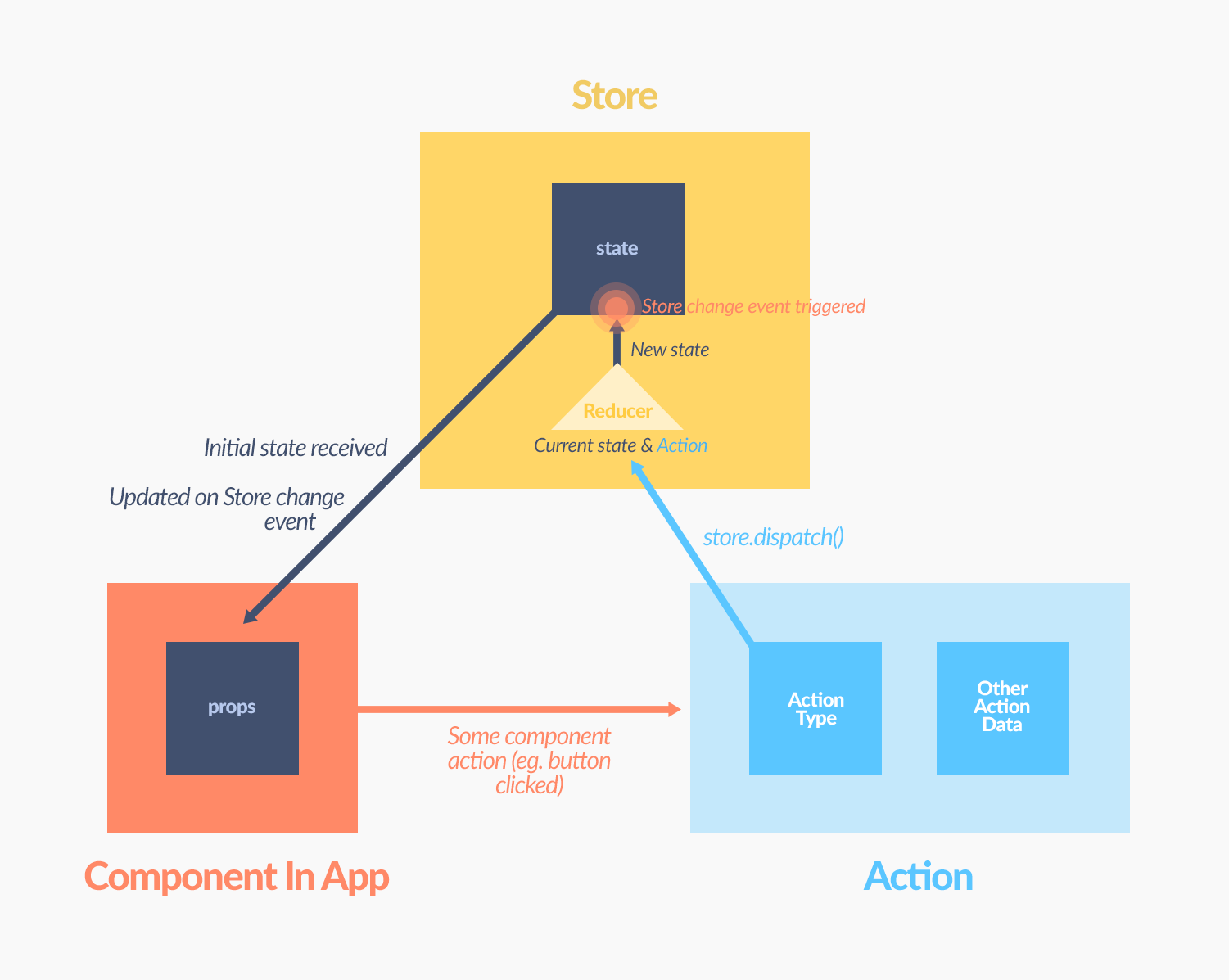

How does the data flow work in Redux? We'll go over this in detail below, but here are the basics:

- React components can cause Actions to be triggered, for example by a button click.

- Actions are an object (containing a

typelabel and other data related to the Action) sent to the Store via thedispatchfunction. - The Store then takes the Action payload and sends it to the Reducers along with the current

statetree (astatetree is the single object that contains allstatedata in a particular structure) - A Reducer is a pure function that takes the previous

stateand an Action, then returns a newstatebased on any changes that the Action might have indicated. A Redux app can have one Reducer, but most apps will end up with several that each handle a different part of thestate(we'll discuss this more below). - The Store receives this new

stateand replaces the current one with it. It's worth noting here that when we say thestateis updated, it is technically replaced. - When the

statechanges, the Store triggers a change event. - Any React components that have subscribed to the change event make a call to retrieve the new

statefrom the Store. - The components are updated with the new

state.

This flow can be summarized in the below diagram for simplicity:

You can see how data follows a clear one-way path, there are no overlapping, opposite direction flows. What this also shows is how clearly separated each part of an app can be - the Store is only concerned with holding the state; the components in the Views are only concerned with displaying data and triggering Actions; Actions are only concerned with indicating that something in the state has changed and including data about what it was; Reducers are only concerned with combining an old state and mutating Actions into a new state. Everything is modular, elegant, and has a clear purpose when it comes to reading the code and understanding it.

There are some other benefits compared to Flux:

- Actions are the only way to trigger a

statechange, this centralizes this process away from the UI components, and because they are properly ordered by the Reducer, it prevents race conditions. statebecomes essentially immutable, and a series ofstates, each representing an individual change, are created. This gives you a clear and easily traceablestatehistory within your app.

Putting This Together

So now that we've talked about the data flow in the abstract, let's look at how our React Native app puts it all to use, and anything we learned along the way.

Store

The Redux docs explain very well how to create a simple Store, so we're going to assume you've read the basics there and skip ahead a little bit, including a few extras with our Store.

Offline Syncing of Store

We've talked before about needing local offline storage of the data, so that the app can operate in low-signal or no-signal conditions (vital at a tech conference!). Luckily, because we're using Redux, there's a very simple module we can use with our app called Redux Persist.

We're also using something called Middleware with our Store - we'll talk more about some of the things we use this for in the testing section, but basically, middleware allows you to fit extra logic in between the point of an Action being dispatched, and when it reaches the Reducer (this is useful for things like logging, crash reporting, asynchronous APIs, etc.).

/* js/store/configureStore.js */

var createF8Store = applyMiddleware(...)(createStore);

function configureStore(onComplete: ?() => void) {

const store = autoRehydrate()(createF8Store)(reducers);

persistStore(store, {storage: AsyncStorage}, onComplete);

...

return store;

}

The nested function syntax might be a little confusing here (some of these functions return functions that take another function as an argument), so here it is expanded a bit:

/* js/store/configureStore.js */

var middlewareWrapper = applyMiddleware(...); // 1

var createF8Store = middlewareWrapper(createStore(reducers)); // 2

function configureStore(onComplete: ?() => void) { // 3

const rehydrator = autoRehydrate(); // 4

const store = rehydrator(createF8Store); // 5

persistStore(store, {storage: AsyncStorage}, onComplete); // 6

...

return store;

}

Here's what's going on:

We activate the middleware using Redux's

applyMiddleware()function (if you want to know more, read the ReduxapplyMiddlewaredocs) which itself returns a function that will 'enhance' the Store object.So we wrap Redux's

createStore()function (with all the Reducers in our app as an argument) in that enhancer function.createStore()returns a Store object for our app,middlewareWrapper()'enhances' it with the middleware, and the resulting enhanced Store object is saved increateF8Store.Then we configure our Store object a little bit.

Persist's

autoRehydrate()is another Store enhancer function (as withapplyMiddleware()that returns a function).We pass it our existing Store object. This

autoRehydrate()takes a Store object previously saved to local storage and automatically updates the current Store with it'sstate.The Persist package's

persistStore()(which we configure to use React Native's built-in AsyncStorage system) is the function that actually takes care of saving the app's Store to local storage. This simple bit ofautoRehydrate()andpersistStore()code is all we need to enable offline sync in our app.

Now, whenever the app loses Internet connectivity, the most recent copy of the Store (including any Parse data we had to grab via the API) will still be there waiting in local storage, and from the user's perspective, the app will just work.

For more information, you can read about the technical details of how the Redux Persist package works, but essentially we're done creating our Store.

Reducers

In the previous explanation of Redux, we mentioned that it introduced a Reducer object. However in each app there can be multiple Reducers, which are concerned with different parts of the state. As a basic example, in a commenting app you might have a reducer related to login status, and others related to the actual comment data.

In our F8 app, we store our reducers in js/reducers/. Here's a condensed look at user.js:

/* js/reducers/user.js */

...

import type {Action} from '../actions/types';

...

const initialState = { // 1

isLoggedIn: false,

hasSkippedLogin: false,

sharedSchedule: null,

id: null,

name: null,

};

// 2

function user(state: State = initialState, action: Action): State {

if (action.type === 'LOGGED_IN') {

let {id, name, sharedSchedule} = action.data; // de-structuring action data

return {

isLoggedIn: true,

hasSkippedLogin: false,

sharedSchedule,

id,

name,

};

}

if (action.type === 'SKIPPED_LOGIN') {

return {

isLoggedIn: false,

hasSkippedLogin: true,

sharedSchedule: null,

id: null,

name: null,

};

}

if (action.type === 'LOGGED_OUT') {

return initialState;

}

if (action.type === 'SET_SHARING') {

return {

...state,

sharedSchedule: action.enabled,

};

}

return state;

}

module.exports = user;

As you might be able to tell, this reducer is involved with login/logout operations, as well as user specific option changes. Let's go through it piece by piece.

Note: we're using ES2015's destructuring assignment to assign each of the left side variables to each of the pieces of the data in the list in

action.data.

1. Initial State

At the beginning we define the initial state, which conforms to a Flow Type Alias (we'll explain more about these in Testing a React Native app). This initialState defines the values - for the part of the state tree that this Reducer handles - that the app will have on first load, or before any previously synced Store is 'rehydrated' as above.

2. The Reducer Function

Then, we write the meat of the Reducer, and it is actually relatively simple. state and an Action (which we will discuss below) are taken as arguments, with the initialState as a default for state (and we're using Flow type annotations for the arguments here, again something we'll cover in Testing a React Native app). Then, we use the received Action, specifically whatever 'type' label it had, and return a new, changed state.

For example, if the LOGGED_OUT Action was dispatched (because the user clicked a log-out button), we reset this part of the state tree to initialState. If the LOGGED_IN Action type happens, you can see that the app will use the rest of the data payload, and return a new state that reflects both standard changes like isLoggedIn, but changes that come from user-inputted data, such as name.

There's one more we'll look at, and that's the SET_SHARING Action type. It is interesting because of the ...state notation being used. This is a more compact and readable alternative to Object.assign() that is part of the Javascript syntax transformers included in React (called the Object Spread Operator), and all it really does in this case is create an object that copies the existing state, and updates the sharedSchedule value.

You can see how simple and readable this Reducer structure is - define an initialState, build a function that takes a state and an Action, and returns a new state. That's it.

We don't do anything else in this function because of the one big rule with reducers, and we'll quote the Redux docs verbatim:

"Remember that the reducer must be pure. Given the same arguments, it should calculate the next state and return it. No surprises. No side effects. No API calls. No mutations. Just a calculation."

One other thing to take notice of: looking at js/reducers/notifications.js there's another reference to the LOGGED_OUT action type; we mentioned this before, but it bears repeating - each reducer is always called after an Action is dispatched, so multiple reducers may be updating different parts of the state tree based on the same Action.

Actions

Let's have a closer look at a login-related Action, and see where it sits in the code:

/* from js/actions/login.js */

function skipLogin(): Action {

return {

type: 'SKIPPED_LOGIN',

};

}

This is a really simple Action creator (the object returned by this creator function is the actual Action), but it lets you see the basic structure - each Action can simply be an object containing a custom type label. The reducers can then use this type to perform the state updates.

We can also include some data payload along with the type:

/* from js/actions/filter.js */

function applyTopicsFilter(topics): Action {

return {

type: 'APPLY_TOPICS_FILTER',

topics: topics,

};

}

The Action creator here receives an argument and inserts it into the Action object.

We then have some Action creators that perform additional logic as well as returning the Action object. In this example, we're also using a custom Action derivative called a ThunkAction (Redux recommends you create something like this to reduce boilerplate) - this special type of Action creator returns a function not an Action. In this case the logOut() Action creator returns a function which performs some logout related logic, and then dispatches an Action.

/* from js/actions/login.js */

function logOut(): ThunkAction {

return (dispatch) => {

Parse.User.logOut();

FacebookSDK.logout();

...

return dispatch({

type: 'LOGGED_OUT',

});

};

}

(Note we're also using the Arrow function syntax in this example)

Async Actions

If, for example, you're interacting with any APIs, you'll need some asynchronous Action creators. Redux on its own has a fairly complex approach to async, but because we're using React Native, we have access to ES7 await functionality which simplifies the process:

/* from js/actions/config.js */

async function loadConfig(): Promise<Action> {

const config = await Parse.Config.get();

return {

type: 'LOADED_CONFIG',

config,

};

}

Here, we're making an API call to Parse to grab some app configuration data. Any API call to a web resource like this will take a certain amount of time. Instead of the Action being immediately dispatched, the action creator first waits for the result of API call (without blocking the JavaScript thread), and then once that data is available, then the Action object (with the API data in the payload) is returned.

One of the benefits of asynchronous calls like this is that while we await the result of the Parse.Config call, other async operations can be doing work, so we can bucket a lot of operations together and automatically improved their efficiency.

Binding to Components

Now, we connect our Redux logic to React inside of our app's setup function:

/* from js/setup.js */

function setup(): React.Component {

// ... other setup logic

class Root extends React.Component {

constructor() {

super();

this.state = {

store: configureStore(),

};

}

render() {

return (

<Provider store={this.state.store}>

<F8App />

</Provider>

);

}

}

return Root;

}

We're using the official React and Redux bindings, so we can use the built in <Provider> component. This Provider lets us connect the Store that we've created to any components that we want:

/* from js/F8App.js */

var F8App = React.createClass({

...

})

function select(state) {

return {

notifications: state.notifications,

isLoggedIn: state.user.isLoggedIn || state.user.hasSkippedLogin,

};

}

module.exports = connect(select)(F8App);

Above we are showing a section of code from the <F8App> component - the parent component of our entire app.

The function above is used to take the Redux Store, then take some data from it, and insert it into the props for our <F8App> component. In this case, we want data about notifications and the login status of the user to be props in that component, and for them to be kept up to date with any Store changes.

We can use the React-Redux connect() function to accomplish this - connect() has an argument named mapStateToProps which takes another function and any time there is a Store update, that function will be called.

So when our app's Store updates, select() will be called, with the new state supplied as an argument. select() returns an object containing the data (in this case notifications and isLoggedIn) we want from this new state, then the connect() call merges this data into the props for the <F8App> component:

/* from js/F8App.js */

var F8App = React.createClass({

...

componentDidMount: function() {

...

if (this.props.notifications.enabled && !this.props.notifications.registered) {

...

}

...

},

...

})

We now have an <F8App> component that will be updated with any new state data that it has subscribed to through the select() function, which it can access through its own props. But how to we dispatch Actions from a component?

Dispatching Actions from Components

To see how we can connect Actions to components, let's take a look at the relevant parts of <GeneralScheduleView>:

/* from js/tabs/schedule/GeneralScheduleView.js */

class GeneralScheduleView extends React.Component {

props: Props;

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.renderStickyHeader = this.renderStickyHeader.bind(this);

...

this.switchDay = this.switchDay.bind(this);

}

render() {

return (

<ListContainer

title="Schedule"

backgroundImage={require('./img/schedule-background.png')}

backgroundShift={this.props.day - 1}

backgroundColor={'#5597B8'}

data={this.props.data}

renderStickyHeader={this.renderStickyHeader}

...

/>

);

}

...

renderStickyHeader() {

return (

<View>

<F8SegmentedControl

values={['Day 1', 'Day 2']}

selectedIndex={this.props.day - 1}

selectionColor="#51CDDA"

onChange={this.switchDay}

/>

...

</View>

);

}

...

switchDay(page) {

this.props.switchDay(page + 1);

}

}

module.exports = GeneralScheduleView;

Again, this code has been heavily simplified for ease of learning, but we can now add and modify code to connect this container component to the Redux store:

/* from js/tabs/schedule/GeneralScheduleView.js */

function select(store) {

return {

day: store.navigation.day,

data: data(store),

};

}

function actions(dispatch) {

return {

switchDay: (day) => dispatch(switchDay(day)),

}

}

module.exports = connect(select, actions)(GeneralScheduleView);

There's a difference this time - we provide the React-Redux connect() function's optional argument, mapDispatchToProps. Basically, doing this merges the action creators inside actions() into the component's props, while wrapping them in dispatch() so that they immediately dispatch an Action.

How it Works

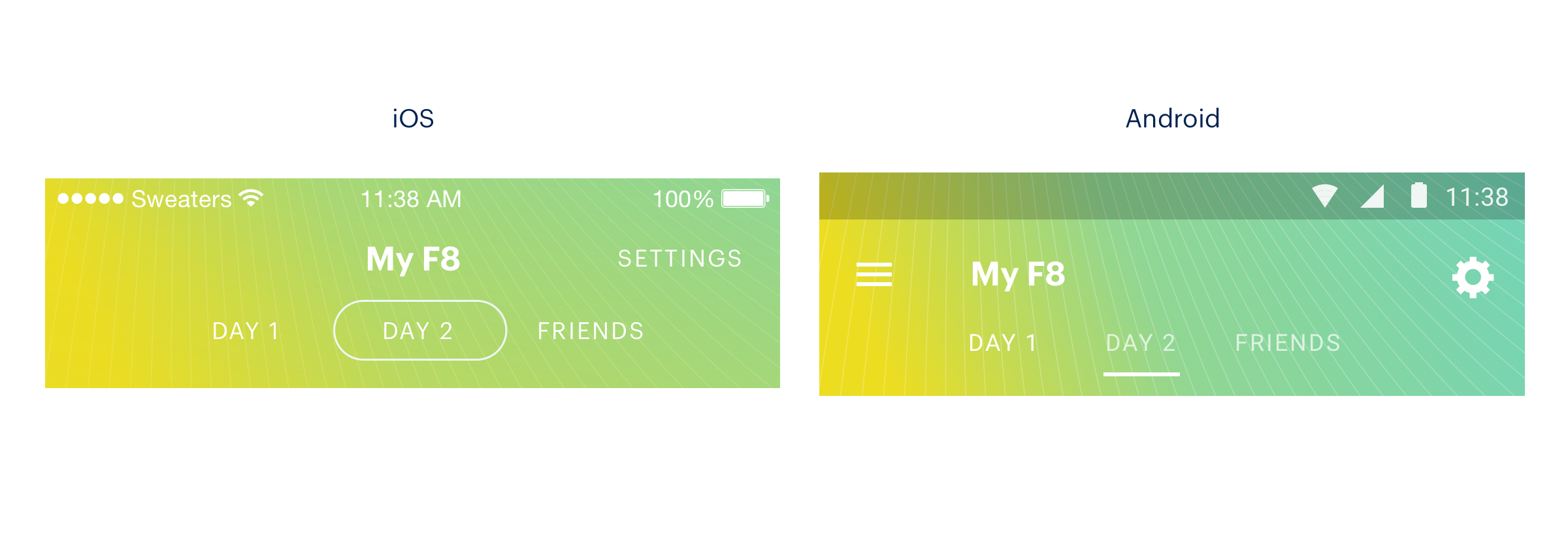

Let's see the actual component:

Tapping on 'Day 1' here would trigger the onChange event in renderStickyHeader(), then the switchDay() function inside the component is called, and that function itself dispatches the this.props.switchDay() action creator. Inside one of our Actions files we can see this action creator:

/* from js/actions/navigation.js */

switchDay: (day): Action => ({

type: 'SWITCH_DAY',

day,

})

And inside the navigation Reducer we can see that this generates a new state tree with a modified day value:

/* from js/reducers/navigation.js */

if (action.type === 'SWITCH_DAY') {

return {...state, day: action.day};

}

The Reducer (and any other Reducers that might be watching for SWITCH_DAY Actions) returns the new state back to the Store, which updates itself and sends out a change event.

And because by connecting <GeneralScheduleView> to the Redux Store we also subscribed it to changes to the state in that Store, the component will now update with the newly changed day value, displaying 'Day 1' schedules.

What about Parse Server?

You've hopefully consumed a lot of new information by now in this tutorial, but let's quickly show how we can connect our React Native app to our Parse Server data backend, and its relevant API:

Parse.initialize(

'PARSE_APP_ID',

);

Parse.serverURL = 'http://exampleparseserver.com:1337/parse'

That's it, we're connected to the Parse API inside React Native.

Yep, because we're using the Parse + React SDK (specifically the parse/react-native package in it), we have incredibly simple SDK access baked right in.

Parse and Actions

Of course, we want to be able to also make queries (for example, inside our Actions)....a lot of queries. There's nothing special about these action creators; they are the same Async Actions we mentioned before. However, because there are so many simple Parse API queries needed to initalise the app, we wanted to reduce boilerplate a bit. Inside our base Actions file, we created a base action creator:

/* from js/actions/parse.js */

function loadParseQuery(type: string, query: Parse.Query): ThunkAction {

return (dispatch) => {

return query.find({

success: (list) => dispatch(({type, list}: any)),

error: logError,

});

};

}

And then we re-use this multiple times very simply:

loadMaps: (): ThunkAction =>

loadParseQuery('LOADED_MAPS', new Parse.Query(Maps)),

loadMaps() becomes an action creator that'll run a simple Parse Query for all the stored Map data, and pass it along - when the query is complete - inside of the Action payload. loadMaps() and a load of other Parse data Actions can be found being dispatched in the componentDidMount() function of the entire app (js/F8App.js), which means the app fetches all Parse data which it is first loaded.

Parse and Reducers

We've cut down repetition in our Actions, but we want to reduce this boilerplate inside our Reducers too. These will receive a bunch of Parse API data from the Action payloads and have to map them to the state tree. We create a single base Reducer for Parse data:

/* from js/reducers/createParseReducer.js */

function createParseReducer<T>(

type: string,

convert: Convert<T>

): Reducer<T> {

return function(state: ?Array<T>, action: Action): Array<T> {

if (action.type === type) {

// Flow can't guarantee {type, list} is a valid action

return (action: any).list.map(convert);

}

return state || [];

};

}

This is a really simple Reducer (with lots of Flow type annotations thrown in), but let's see how it works with the child Reducers based off of it:

/* from js/reducers/faqs.js */

const createParseReducer = require('./createParseReducer');

export type FAQ = {

id: string;

question: string;

answer: string;

};

function fromParseObject(map: Object): FAQ {

return {

id: map.id,

question: map.get('question'),

answer: map.get('answer'),

};

}

module.exports = createParseReducer('LOADED_FAQS', fromParseObject);

So instead of repeating the createParseReducer portion of the code each time, we're simply passing an object to the base Reducer that maps the API data to the structure we want for our state tree.

Now we have an app with a well-structured and easy to understand data flow, connection to our Parse server, and even offline syncing of our Store to local storage.